Chemical injuries of eye—A review of 75 cases from West Mala

【摘要】 To determine the nature of chemicals involved, type of occupation most at risk, severity of ocular injury, complications and visual outcome in patients with chemical injuries of eye.METHODS: In a retrospective study gender, age, race, occupation of patients, nature of chemical, eye involved, vision at admission, severity of ocular injury, complications and visual outcome were noted from the case records. RESULTS: Among 75 patients reviewed 90.3% of patients were males; 84% were in the working age group (21-50 years); 29.3% were factory workers; 52% suffered from alkali injuries; 65.4% were factory/construction workers; 57.3% had both eyes involvement; 9.3% of the affected eyes had vision <6/60 at admission; 72% of injuries were of grade I nature; 19.5% of the affected eyes developed complications such as dry eye, vascularization of cornea, corneal opacity, complicated cataract, secondary glaucoma etc.; final outcome of vision 6/18 or better was achieved in 92% of eyes; blindness was noted in 6.2% of the affected eyes. CONCLUSION: Even though chemical injuries commonly involve both eyes, in majority of them they are mild in nature with good visual outcome. Immediate copious irrigation of the eye will help in reducing the severity of chemical injury. Appropriate emergency treatment will reduce the long term complications and visual impairment. However, severe chemical burns of the eye can result in blindness in some cases.

【关键词】 chemical injuries; acid burns; alkali burns; complications; blindness

INTRODUCTION

Chemical burns of the eye represent a significant proportion of ocular injuries in ophthalmic practice requiring emergency treatment. If not, they may produce extensive damage to the ocular surface and result in visual impairment. In some severe cases they may penetrate into the eye damaging the anterior segment structures resulting in complications. Most of the injuries with acids tend to confine to the ocular surface unlike alkalis that often carry a poor prognosis because of their deep penetration into the eye. People working in industrial factories are more prone for these injuries. However, house hold detergents/cleaning agents, paints, lime, cement falling in the eyes resulting in chemical injuries are not uncommon.

Many studies are available from different Western countries on chemical injuries/burns of eyes in the literature [1-11]. However, the pubmed search did not reveal any published data on chemical injuries of eye from Malaysia or surrounding countries. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to determine the nature of chemicals involved, type of occupation most at risk, severity of ocular injury, complications and visual outcome of chemical injuries in patients treated in University of Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of the case records of patients admitted for chemical injuries of the eye in UMMC over a period of ten years (1997/2006) was done. Gender, age, race, occupation of patients, nature of the chemicals involved, presenting ocular features, visual acuity at admission, severity of ocular injury, complications and visual outcome following treatment were noted from the patient's record. When the patient was not sure about the type of the chemical, the nature of the chemical (acid or alkali) was decided after doing litmus paper test which indicates the pH of the tears. The chemical injuries were graded depending on the clinical findings into four grades according to the Roper-Hall modification of the Hughes classification system [12]—Grade I: corneal epithelial damage without limbal ischaemia, Grade II: hazy cornea but visible iris details and with ischemia affecting less than one third at limbus, Grade III: total loss of corneal epithelium; stromal haze obscuring iris details and ischaemia affecting between one-third to one-half at limbus, and Grade IV: opaque cornea obscuring the view of the iris and pupil and ischaemia affecting more than one-half at limbus.

Treatment given to all patients was of standard protocol for chemical injury which included immediate copious irrigation of the eye with normal saline until the pH of tears came to near neutral level, removal of foreign particles present (cement, lime, plaster etc.) on the cornea/ conjunctiva, topical dexamethasone, ciprofloxacin, homatropine, artificial tears, oral Vitamin C, and oral Doxicycline. Timolol eye drops and Tab. Acetazolamide were given whenever there was raised intraocular pressure. Patching of the eye was done depending on the size of corneal epithelial defect. Bandage soft contact lens usage or tarsorrhaphy was done in eyes with persistent epithelial defect. During the follow up at regular intervals the complications if any present and best corrected visual acuity were also noted from the patient's record. The results were analyzed using SPSS programme.

RESULTS

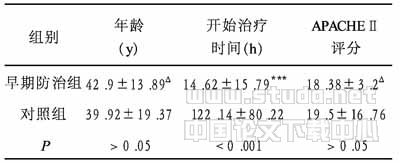

A total number of 75 patients were treated over a period of ten years. Majority of the patients were males (68, 90.3%). The age of patients ranged between 11 and 67 years; 63 of them (84%) were in the working age group (21-50 years); only 5 (6.6%) were below 20 years age. Twenty seven patients were Malays (36%), followed by Chinese (20, 26.7%), Indians (11, 14.6%) and 17 (22.6%) were other nationals who were industrial/construction workers i.e. 13.3% Indonesians, 8% Bangladeshis, 1.3% Nepalese.

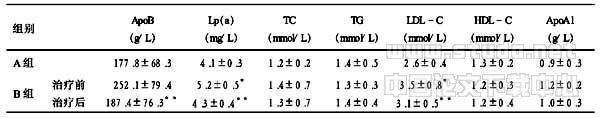

Majority of the patients (46, 65.4%) sustained accidental injuries at factories and construction sites (Table 1). In 8 of them (10.6%) the chemical burns were due to assault by unknown persons. In our study, alkali injuries (39, 52%) were more common than acid injuries (22, 29.3%); the remaining (14, 18.7%) were due to miscellaneous substances (Table 2). Thirty eight patients (50.6%) initially attended private general practitioner clinics and then referred to our hospital after preliminary treatment; 8 patients (10.6%) went to nearby private hospitals and then came to us; while 29 patients (38.6%) came directly to accident and emergency department of our hospital.

Forty three out of 75 patients (57.3%) suffered bilateral injuries. Thus, a total of 118 eyes were affected in 75 patients. The majority of ocular injuries (85 eyes, 76%) were Grade I in nature, while severe injuries of grade IV were seen in 2.5% of eyes (Table 3). Varying degree of chemical burns on one or both eyelids was seen in 20 patients. In addition to ocular injuries, there was involvement of other structures of the body in 11 patients --- face alone in 6 patients, face/ neck in 2 patients, face/ chest in 2 patients, and face/ hands in 1 patient. At the time of admission vision was normal in 19 (16.1%) eyes, and poor (<6/60) in 11 (9.3%) eyes (Table 4).

Since the vision was good after the treatment many patients did not turn up for long term follow up. The follow up period ranged between 1 week and 17 months (1 week: 39 cases, 2-4 weeks: 17 cases, 1 -3 months:11 cases, 4-12 months: 4 cases, >12 months: 1 case). Three patients (2 patients with both eyes involvement and 1 patient with right eye involvement) left the hospital against medical advice on the evening of admission since their vision was good and there was financial problem for paying hospital charges. Therefore, the complications and final visual outcome were noted in 113 eyes only. One or more complications were seen in the affected eyes at the time of discharge/ during follow up in 22 out of 113 (19.5%) affected eyes; dry eye being the most common complication (Table 5). The best corrected vision at the last follow up was 6/18 or better in 104 (92%) eyes, while 7 (6.2%) eyes became blind (Table 6). The blindness was consequent to alkaline injuries in 5 eyes and acid injuries in 2 eyes.

DISCUSSION

The chemical injuries to the eye usually occur due to external contact with chemicals under following circumstances: (I) factories-acids, alkalis during storage/ transportation (II) construction sites-cement, mortar, (III) domestic accidents ?ammonia, solvents, detergents, paints, vinegar (IV) agriculture accidents-insecticides, fertilizers, (V) chemical laboratory accidents-acids, alkalis, (VI) mechanic workshops ?battery acid, (VII) deliberate chemical attacks (assault)-acids, alkalis, (VIII) chemical warfare injuries-mustard gas, (IX) self inflicted in malingerers and psychopaths-acids, alkalis.

Varying number of cases have been reported from different countries in the literature i.e. 63 from USA[1] , 172 from Finland[2] , 180 from UK[3] , 102 from India[4] , 171 from Germany[5], 121 from Australia[6], 12 from Nigeria[7], 269 from Norway[8], 66 from France[9], 36 from Japan[10]. The frequency of chemical injuries depends upon the country/region, number and variety of industries, protective/preventive measures practiced at the work site, and medical facilities available in the place of study.

The information on the nature of chemicals involved has seldom been reported from developing countries where safety requirements in handling hazardous chemicals are still loosely enforced. Over the past three decades, Malaysia is moving away from an agricultural society to a more industrialized nation. As such, we expect a lot more of factory work related injuries. In the capital city of Kuala Lumpur there are two more tertiary hospitals (one Ministry of Health apex hospital and another teaching hospital of National University of Malaysia), and few corporate hospitals with eye departments. Some of the patients with chemical injuries might have gone to those hospitals for treatment. This could be the probable reason for the small number of cases in our review of ten years study.

In the present study, males outnumbered females similar to the other published reports[1, 3-5, 8, 12]. In 57.3% of patients both eyes were involved in chemical burns in our series. A slightly higher percentage of bilateral involvement was reported by Merle[9] and Kuckelkorn[5], while Klein and Lobes[1], Saini and Sharma[4] reported much lower figures of the same. There is a high preponderance of ocular chemical injuries in working age group people in our country (84%) and this type of morbidity often affects the economic status of these patients and indirectly the economy of the country. In our study, alkali burns (52%) are more frequent than acid burns (29.3%) which is similar to earlier reports [2, 8] of the same. However, Saini and Sharma[4] reported higher frequency of acid burns than alkali burns.

The people working in factories (42.7%) and construction sites (22.7%) were more commonly affected than other occupations. Similar to our results, Kuckelkorn et al[13] from Germany reported 73.8% industrial accidents and 30% in builders and labourers. The high incidence of accidental injuries in our factory and construction site workers indicates that efforts for preventing such injuries in our country should be concentrated in these places. The frequency of assault chemical injuries (10.6%) in our series was similar to 10.5% reported from UK[3], but much lower than 45.5% from France[9], and 83.3% from Nigeria [7]. The occurrence of domestic accidental chemical injuries in 9 (12%) patients in our series is much lower than the same reported from other countries i.e 23% from France[9], 28% from Norway [8], and 37% from Germany[5].

It is also interesting to note that 50.6% of chemical injuries were seen first by general practitioners before the patients were referred to ophthalmologists. This suggests that general practitioners could play a prominent role in minimizing the injuries by administering preliminary treatment. Lesser extent of ocular damage, better visual outcome and shorter duration of hospital stay has been reported in patients treated with immediate copious irrigation[2,10]. This sort of management can be easily carried out by general practitioners who are often the first to be approached for medical treatment in these injuries.

In our series, grade III and IV injuries were seen in 12 out of 118 eyes affected (10.1%). In contrast to this, a much higher percentage of patients, 27.6% from Australia[6] and 35.9% from India[4] suffered from such severe chemical burns among the affected eyes. The general observation is that such severe injuries are more common in assault cases because the victim's eyes are specially targeted in them. In our series, 4 eyes of grade III and 2 eyes of grade IV burns (50% of total grade III and IV injuries) were noted in assault chemical injury cases.

The complications were seen in 19.5% of the affected eyes in our study. In a series of 12 chemical injury (10 assault and 2 accident) cases in Nigeria[7], complications were seen in a larger proportion of cases i.e corneal opacity in 10 patients, symblepharon in 9 patients, bilateral blindness in 4 patients and unilateral blindness in 6 patients. Late presentation to hospital and failure to initiate adequate first aid treatment were contributing factors to the poor outcome in that study. Blindness was noted in 6.2% of the affected eyes in our series, and the Indian study [4] also reported 7% of the eyes became phthisis bulbi (blind). However, a much higher percentage of blindness (57.4%) was reported in the study from China [14].

The ultimate visual prognosis in chemical injuries depends on the degree of severity of injuries at the initial presentation. In the present series, 77% of eyes achieved a visual acuity of more than 6/12, and 0.9% had no light perception. In the USA study [1] where most of the cases were due to assault, only 29% achieved a visual acuity of more than 6/12, while 18% had no light perception. The visual achievement reported in the Indian study [4] was more than 6/12 in 76% of eyes and 7% of eyes became phthisical (no perception of light).

Based on the results of our series, it is evident that people working in factories and construction site in our country are more prone to accidental chemical eye injuries. Health education to the administrators in these two fields has a great role in reducing the frequency of such injuries. They should be explained about careful handling of dangerous chemicals at work site and the usefulness of adequate protection of eyes by wearing special goggles. The public must be made aware of the dangerous properties of acids and alkalis and legislation should be implemented to prohibit the over-the-counter sales of such chemicals. Health education on first aid measures at the scene of the accident must also be emphasized. Initial copious irrigation with water at the work site, can be of paramount importance in limiting the severity of the injuries. The posters with self explanatory figures about irrigation methods will be of much use at the work sites. Since 61.2% of our patients presented first to the general practitioner clinic/ outpatient departments of private hospitals, the non-ophthalmologists must be educated well on the importance of immediate and copious irrigation with sterile solution (normal saline) and removal of all solid particles, even before taking the detailed history and performing eye examination.

Most of the chemical injuries are mild in nature and involve both eyes. These injuries are seen more often in industrial and construction workers. Immediate copious irrigation of eyes will reduce the severity of injury with chemicals. Appropriate immediate treatment of severe cases will reduce the long term complications and visual impairment. Public education and practice of protective measures at the work site will help in reducing the frequency of chemical injuries.

【】

1 Klein R, Lobes LA Jr. Ocular burns in a large urban area. Ann Ophthalmol , 1976;8:1185-1189

2 Saari KM, Leinonen J, Aine E. Management of chemical eye injuries with prolonged irrigation. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl ,1984;161:52-59

3 Morgan SJ. Chemical burns of the eye: causes and management. Br J Ophthalmol ,1987;71:854-857

4 Saini JS, Sharma A. Ocular chemical burns: clinical and demographic profile. Burns ,1993;19:67-69

5 Kuckelkorn R, Luft I, Kottek AA, Schrage NF, Makropopulos, Reim M.. Chemical and thermal eye burns in the residential area of RWTH Aachen. Analysis of accidents in 1 year using a new automated documentation of findings. (article in German). Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd ,1993;203:34-42

6 Brodovsky SC, Mc Carty CA, Snibson G, Loughnan M,. Sullivan L, Daniell M, Taylor HR. Management of alkali burns: an 11-year retrospective review. Ophthalmology ,2000;107:1829-1835

7 Ukponmwan CU. Chemical injuries to the eye in Benin city, Nigeria. West Afr J Med ,2000;19:71-76

8 Midelfart A, Hagen YC, Myhre GB. Chemical burns to the eye (article in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen ,2004;8:49-51

9 Merle H, Donnio A, Ayeboua L, Michel F, Thomas F, Ketterle J, Leonard C, Josset P, Gerard M. Alkali ocular burns in Martinique (French West Indies): Evaluation of the use of an amphoteric solution as the rinsing product. Burns ,2005;31:205-211

10 Ikeda N, Hayasaka S, Hayasaka Y, Watanabe K. Alkali burns of the eye: effect of immediate copious irrigation with tap water on their severity. Ophthalmologica ,2006;220:225-228

11 Roper-Hall MJ. Thermal and chemical burns. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK ,1965;85:631-653

12 Beare JD. Eye injuries from assault with chemicals. Br J Ophthalmol ,1990;74:514-518

13 Kuckelkorn R, Makropoulos W, Kottek A, Reim M. Retrospective study of severe alkali burns of the eyes. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd ,1993;203:397-402

14 Li GH. Clinical analysis of 107 cases with chemical burns (article in Chinese). Zhonghua Zheng Xing Shao Shang Wai Ke Za Zhi ,1990;6:34-35,76